| Homepage |

| New books |

| News in Brief |

| list of late magazines |

| Articles Recommended |

Articles Recommended |

|

|

Unique Illustrations in Tibetan Buddhist Sutras

By Qu Yaofei

Yoga figures

The illustrations for Tibetan sutras are coloured in two ways: in black and white or colours - the monotone illustrations accompanying Tibetan characters and usually engraved on woodblocks. The illustrations are often showed on the cover pages or two sides of the head pages of sutras; they are frequently displayed at two frames and in the middle of end pages. In this paper, I am going to introduce the illustrations in the sutra book entitled "Eight Thousand Odes". The book is also given the title "Eight Thousand Prayers of Prajna". This is a woodcut book that I believe features a unique art style by including a large number of illustrations. Two different figures are regularly presented on both sides of each page. In total, the book contains 1000-odd illustrations.

With a total of 24 volumes, including 32 sections, the book has been translated into Tibetan by Indian scholars (Shakya Sena and Kyana Siddhi) and a Tibetan translator (Lotsawa Dhashila). It is quite popular book amongst Tibetan Buddhist believers, and almost every family keeps it in family shrine in order to offer frequent family sacrifices and recitation. They believe the superhuman strength of the sutra will bless their family member with safety, peace, and good fortune.

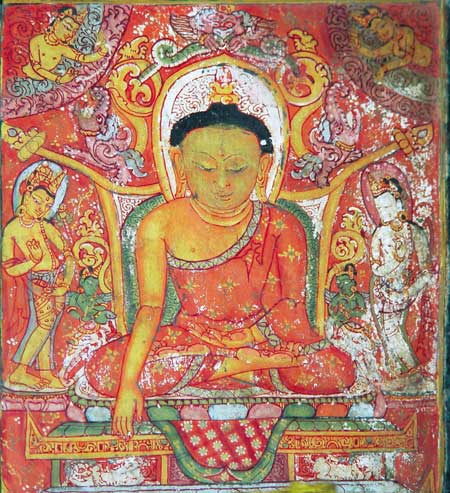

Shakyamuni

The illustrations in this sutra usually include the figures of Buddha, Bodhisattvas, Avalokitesvara, Tara, accomplished monks, and figures of outstanding merit and virtue. In accordance with religious requirements, sketching or shaping all of these figures must strictly follow the rules prescribed in the "Statue Measurement Sutra", in particular such figures as Buddha, Bodhisattvas, Avalokitesvara and Tara. This includes the postures, quality, hand pose, and even the accessories worn by those figures. All instructions of measurement are illustrated in detail through religion law. Any violation of standards would be regarded as disgracing Buddha; in addition, the directions on sculpturing, sketching and modeling are believed to be part of Buddhist religion rituals. That is why it is requested to strictly follow the directions.

Before the 1950s of the 20th Century, most of Tibetan painters were lamas. By focusing on religion as their specific purpose in painting, they usually practiced a series of rituals before they really started to paint; namely, to burn incenses, recite universal mantra, touch and count Buddhist beads. All those activities aimed to provide a discipline. In addition, painters were particularly asked to adopt exclusive characteristics so that they could be differentiated from ordinary people. In sutras, it says: "as a painter, he must characterise himself as a welldoer; for instance, a painter should be a follower of Buddhism; he should not be reserved, irritable and greedy but rather benevolent, studious, and refraining from indulgence??"

Dhorje

Nevertheless, maintaining such purity of heart and an unquestioning belief in religion on the part of the painters, means the Buddhist figures drawn by those painters are at a distance from mainstream art. Surely, we should not judge religious painting by simply adopting orthodox art standards, but rather we are constantly inspired by the religion, which touches our basic sense of empathy and pity so that we could make the world where we live, become a better place

In the book of "the Eight Thousand Odes", the art is fully devoted to religion; religious doctrine is disseminated through the language of kindness, wisdom, bravery, and even fear, which could actually resonate with believers through graphic and sculptural arts. Nevertheless, nothing is ever as hard as steel; to some extent, flexibility always exists everywhere. So does religious painting. Amongst the woodcut illustrations in the book of "the Eight Thousand Odes", the painters either unconsciously or intentionally show their flexibility in choosing materials and adopting unique methods of painting, in which the pictures are simply but creatively executed. There is much variety in the depiction of Buddha, including historical religious figures representing incarnations of wisdom, strength, power, and knowledge.

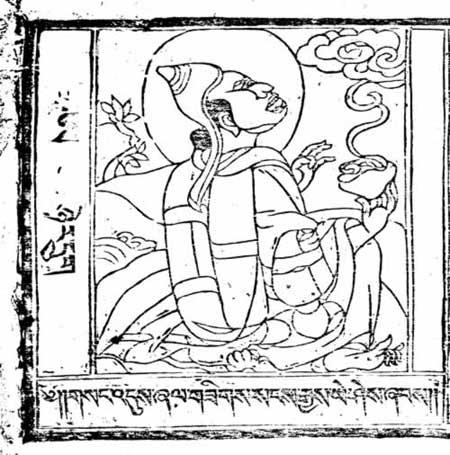

Seeing Personal Tantric Deity Sangye Yeshe

In addition, the individual painter, as a pious religious believer, features in different aspects such as ability and insight into religious figures (including the extent of comprehension, intuition, and so forth). Individual painters show their distinct characteristics by their different approached to portraying religious figures while sketching and drawing pictures. That is why we see such bizarre and even whacky depictions of figures in the illustrations of this book. For instance, the figure of "enlightenment" is sketched with such exaggerated design and bizarre expression; the experience of viewing it is like an apotheosis. The painters have achieved a perfect interface between humanity and divinity, fully exploiting the extremes of expressionism and symbolism. They also applied illusionary plastic art and radical imagination. Originating from India, the "Eight Thousand Odes" provides us with an insight into Indian arts. For example, we can see Indian apotheosised fairies and Yoga figures in abstractive poses and with unearthly expressions.

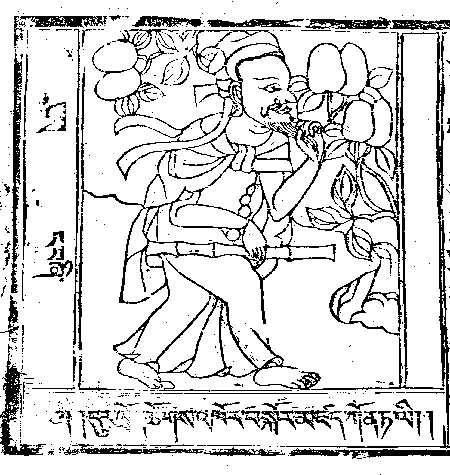

"Black-line engraving" is a printing method of primitive simplicity. The outstanding feature of such printing is that the lines are unadorned and simple. It looks free and easy with a unique format. The pictures convey a feeling of both falsity in one way but truth in another. The smooth lines show emotion and vitality; by ignoring the general adorned background of Tibetan painting, we can easily appreciate the sentiments and dynamics in the illustrations.

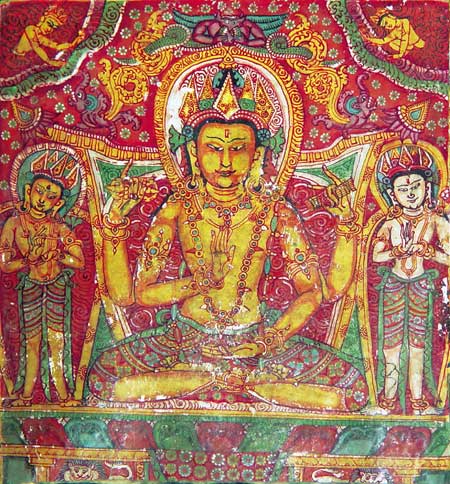

Great mother of Prajna

Illustrations of the Sutras usually adopt "black-line engraving" to engage our vision with the communication between the lines through spaces, transitions and artful rhythm. Accompanying multiple reprinting on specific papers (Sutra books are usually not bound to facilitate easily reading - that is why the paper is often thick and rough.) the lines are perfectly reproduced to show their unique beauty and vigor in terms of light and dark, falsehood and reality, long and short, smooth and rough, hiding and revealing, firm and soft, and order and chaos. What a clever device to make you feel the subtle implication beyond the drawing! In the book "Eight Thousand Odes", readers usually enjoy the extremely simply lines in a picture like "Officer Dali in Slta Vana" and the exaggerated style of a picture of "Seeing Personal Tantic Deity Sangye Yeshe".

Apart from the monotone illustrations, there are also coloured illustrations in sutras.

The difference between monotone and coloured illustrations does not only exist, but also the use of hand painting is one of the specific features of the coloured illustrations.

Just like a fresco, hand-painted illustrations usually show different styles based on different geographic locations and variety of painting schools. In addition, due to constraints on format and physical space in the sutra book, the handmade paintings don't often convey a complex scene of story. Here I would like to introduce two illustrations by painters from Tsang Region in about 12th Century. Observing the format, we find the picture design closely resembles Thangka's art; namely, they follow the same standard format. For example, the leading Buddha is large scale and placed at the centre looking sublime, but side Buddha (secondary Buddha) are symmetrically standing to one side of the leading Buddha in a smaller scale. On viewing the style of illustrations of Sakyamuni, it is easy to see that both the leading and side Buddha are sketched with big shoulders but slim waists, high chests but soft bellies in a precise ratio; it makes the Buddha look not only sober but also elegant. With a slightly over-sized head, all other parts of the leading Buddha are depicted in proportion; the head of the leading Buddha is slightly declining with stateliness of facial expression and in a look of contemplation. With a half-opened eyes cast down, his round lip tend to be apart, which make him appear alive and natural. The right hand points vertically and presses the subdued demons to the ground. This gesture tells us the story that Sakyamuni went through tribulations and faced down many demons before he was enlightened and then finally became Buddha.

officer Dali in Slta Vana

The picture shows Sakyamuni sitting cross-legged on the lotus throne, which consists of double-layer petals shaped in wide top but narrow at the bottom. White lions are drawn at the bottom of the throne as protectors. The side Buddha is designed in the typical Indian style of Gandhara through the depiction of poses, accessories, clothes and also gauffers. The most noticeable are the elegant standing poses of semi-nude female figures, including heads, chests, and bellies, which are depicted in the classical way of drawing and posed with three flexes; the head tilts to the right side, chest to the left; the hip is tending to the side but lifting, and two legs turn to the right. They look delicate and charming. The round bodies in the exaggerated drawing style look sprightly and vigorous.

Following the same format as frescoes, sculptures, and Thangka within Tibetan Buddhist art, the painters also paint three circular wrinkles on the neck of Sakyamuni in this illustration. The wrinkles are not only in a favorable way to depict the length of the neck but also to make you feel the neck is elegant and beautiful. I still remember one of my university teachers instructing us in his brilliant views on how to draw a female's neck. He always stressed that it was of importance to sketch the "three beautiful round wrinkles" of the female. I believe that might be a common oriental view on aesthetics.

Accomplishment sage on exoteric and esoteric practice

The other illustration I would like to mention here is the coloured picture of the "Great Mother of Prajna". Her upper body is nude but wearing jade-like stone with a five-leaf coronet on her head, her facial expression shows sublimity and dignity, but the up-turned corners of her mouth make you feel her compassion. With her left hand on the main arm, she poses in a meditation gesture and the right hand positioned in a charity mudra. On her other arm, the left hand raises up the sutra of Prajna Paramita and right hand holds a diamond; sitting cross-legged on a lotus throne, her legs are tightly together with her precious clothes and bright gauzy silks fluttering around her waist. The earrings, together with arm ring and shoulder bracelets, make her look magnificent and elegant. Drawing flower patterns to replace the clothes wrinkles, the painters successfully sketch out a clear shape of the legs and make you feel she is gliding. The side Buddha stands at both sides in full face; they all look rather subtle but meaningful. However the painting is not exaggerated to the same extent as the one mentioned above. In this picture, the legs of the side Buddha are more likely to be sculptured and exhibit classic simplicity. Such a standing pose is quite common in other areas of Tibetan Buddhist art. Looking at this picture, we can easily see that all adornments, no matter on the body of the leading Buddha or side Buddha, are executed in the manner of the miniature painting of Persia. Taking red colour as the principal colour, the picture also has added details with green, white, yellow and black; against the heavy, warm colour the white is used for refreshing, black for interspersing, yellow acting as accessory for replacing gold colour in order to make it bright, and green to contrast with red. All colours match one another in a harmonious way. Set off by the black, all colours seem lustrous.

In the background of the above-mentioned pictures, the door frame is adorned in Indian style and the top of the doorpost stretches to the edges of the images. A golden armed roc is painted at the top of the leading Buddha's head. The roc acts as protector with two fierce staring round eyes; its claws are tightly grasping a long snake with beaked mouth, while its body is flying downwards, looks extremely striking. After an arabesque is drawn to surround the leading Buddha, the side Buddha, the roc, and the protectors, the entire picture becomes vivid and moving.